Post-crash care is one of the five key components in the safe system approach that aims to reduce the number of deaths and serious injuries on the road. While the other four components centre around the prevention of crashes, post-crash care tries to continue to save lives after the crash. Figure 1 below shows the five components of the safe system approach.

Around 50% of the people who lose their lives on the road die within the first few minutes after a crash or during the ride to the hospital1. Even after their arrival at the hospital, time remains crucial: 15% of the victims die within the first four hours. These numbers are even higher for low and middle-income countries, where the proportion of road victims who die before reaching the hospital is estimated to be at least twice as high2.

For those who get injured, road crashes can severely impact their physical and mental health and create long-term conditions that can restrict their ability to function normally in their work and personal lives. Fast and high-quality emergency care is necessary and must stretch across all actions, including the reporting of the crash, the road to the scene, the extrication from the vehicle, the care at the scene, the transport, and facility-based emergency care.

Getting to the crash

In the field of emergency care, the term ‘Golden Hour’ is often used to highlight the importance of giving Basic Life Support (BLS) within the first 60 minutes to give the victim the best chance of survival. Once the crash has happened, the emergency services should be called as quickly as possible, either via the victim themself or bystanders or via the eCall system.

Since 2018, eCall has been integrated in all new vehicles and will contact the nearest emergency response centre automatically after a severe car crash. It communicates the exact location and time of the impact and the vehicle’s identification number. The eCall system can accelerate the emergency response by 40% in urban areas and 50% in rural areas3.

The time that is needed for the emergency services to reach the scene of the crash depends strongly on the country and specific location. The European project Baseline, funded by the European Commission, investigated the time elapsed between the emergency call and the arrival at the scene and discovered that this can vary between 18 and 54 minutes4. Response times are often the longest on rural roads and shortest during daytime during weekdays. In the case of a crash on a highway or other busy road, response times can be delayed due to traffic jams. If a traffic jam occurs, road users should create a rescue lane to give emergency services space to pass through. However, these lanes are often not wide enough (at least 3 meters), are only created once an emergency vehicle appears, or are not known by foreign drivers. Therefore, national and international awareness campaigns, such as the one organised by Excellence in Road Safety Award winner from Slovenia, remain imperative. Find out more here

Extrication of road crash victims

Once the emergency services have arrived on the scene, close collaboration between the different services is crucial to secure the scene and remove the victim as quickly and safely as possible. A victim can be entrapped medically (e.g., injuries or spinal immobilization), physically, or a combination of both.

As well as the ‘Golden Hour’ concept, the firefighters also consider the ‘Platinum Ten Minutes’. This concept focuses on the crucial moment in which emergency services assess the situation and start the initial treatment and extrication of the victim. In case of signs of life-threatening ventilation problems or bleeding into the skull, chest, abdomen, or pelvis that require urgent surgical intervention, this should be done within the first ten minutes.

In all road crashes, the same stages of rescue are followed5:

- Establishment of the scene safety and contact with the victim(s) to ensure airway control and protection of the cervical spine.

- Stabilization of the vehicle and glass management.

- Gain of entry to the vehicle and continuing stabilization of the casualty.

- Space creation to provide casualty extrication.

In the ideal situation, firefighters can make the first cut in the vehicle within the ‘Platinum Ten Minutes’. However, this is very dependent on the type of rescue that is needed and possible. Traditional extrication that focuses on movement mitigation normally takes around 30 minutes. A crucial factor that is often considered when deciding on the extrication method is the risk of exacerbating potential spinal injuries. However, avoiding this risk brings delays in the rescue time. Research has shown that only around 0.7% of the car crash victims have a spinal cord injury, and over half of them also have additional severe injuries that require time-sensitive interventions6. Nonetheless, the position of the victim in the vehicle makes it difficult for the medical staff to complete a detailed assessment of the victim’s condition.

Another element that must be considered and avoided at all costs when making the assessment is the potential risk of sudden deterioration at the point of release (possibly due to clot disruption).

Based on the condition of the victim and the ability to provide both a safe working environment and safe working practice, there are three rescue types5:

- Snatch rescue: this rescue is used when there is an immediate threat to the safety of the victim (e.g., fire), or if the victim is in cardiac arrest. Extrication has priority above all other actions, and the victim is, if possible, pulled from the wreckage within a few seconds.

- Rapid extrication: the rescue needs to be done within the Platinum Ten Minutes, but the victim must be extricated laterally via a rescue board to avoid further damage.

- Controlled release: The victim is stabilized, and the firefighters can give priority to technique and comfort.

Advancements in vehicle safety

The protection of car drivers and passengers in case of a crash has improved significantly over the last century. The enhancement of structural integrity has led to less significant collapse of the passenger compartment and intrusion of the steering wheel and dashboard7. The introduction of restraint systems such as airbags and seatbelts for both driver and passenger protect them from the impact caused by a crash.

However, these elements, together with the overall improvement of the strength of the material used to build the vehicles, increase the challenges and dangers for both firefighters and those trapped inside when extrication is necessary. With the arrival of electric vehicles, rescue teams are faced with the uncertainty and danger of battery systems that are made of various flammable materials. A battery that has been drenched with water after a crash and is not discharged correctly can still retain a dangerous voltage level several months later.

Therefore, it is crucial that firefighters have enough knowledge about the vehicle to make a correct assessment of the situation and their extrication plan. Rescue sheets, developed by Euro NCAP in collaboration with the car brands, summarize all the crucial information on the specific vehicle (e.g., location of airbags, high-voltage cables, best possible places to cut). These sheets are put together in the Euro Rescue app, which can be used by firefighters both online and offline. Our recent video case study explores the importance of access to this information and the development of the Euro Rescue app by Euro NCAP. Watch it below…

Emergency medical care

The medical staff present at the crash will assist the firefighters with the assessment of the condition of the victim, the delivery of Basic Life Support (BLS) to stabilize their condition, and if possible, give emotional support and the decision on the preferred extrication method. Once the victim is extracted from the vehicle, they will decide on the type of pre-hospital care they will give before they return to the hospital. There are two philosophies considered8:

- Stay and Play: care is prioritized over transport. It is perceived that the patient cannot be transported without being (further) stabilized. The quicker the treatment is started, the less compensatory systems the patient will use, limiting shock and increasing the chances of survival and autonomy.

- Scoop and Run: The victim is in need of specialized care and must go to the hospital as quickly as possible. Care will be limited to BLS and should not delay the transport. This is mostly limited to cases in which there are certain traumatic, obstetric, or cardiovascular injuries and an immediate surgical procedure is necessary.

The decision on the type of intervention also depends on the level of competence of the staff, the place of the intervention, the proximity of the hospital, and possible dangers.

Bystander medical care

Regardless of the type of care chosen, Basic Life Support (BLS) needs to be given to all victims as fast as possible. A car crash is often witnessed by bystanders who can perform a variety of activities that can increase the survival chances of the victim(s). They can contact the emergency services, increase the safety of the scene, give emotional support to the victim, attempt to stop bleeding and perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

However, bystanders can have various motives not to start or assist with BLS9:

- Perception: Bystanders will only act if the injury is perceived as serious enough

- Fear: Fear of liability, fear of infectious diseases or fear of doing something wrong and further harming the victim can discourage bystanders to help

- Knowledge: If bystanders have knowledge of first aid, they are more likely to see the benefit of giving first aid and perform it correctly

- Relationship to the victim: Bystanders are more likely to perform first aid to someone they know

- Number of bystanders: The more people present at the scene; the less likely individuals are to provide assistance

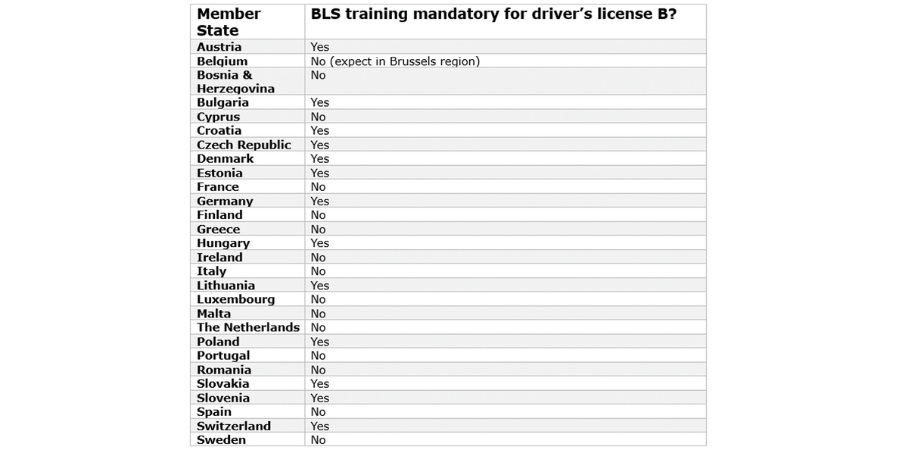

One way to increase the likelihood of bystanders helping victims is to provide BLS training. This will help them better analyse medical conditions and dangerous situations, anticipate the needs of the victim(s), give emotional support and feel more confident in giving BLS. In 13 Member States, BLS training is a mandatory component of the driver’s license B10. Various organisations, such as the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) and European Driving Schools Association (EFA), have developed awareness campaigns to inform all road users about the importance of this topic and encourage them to follow courses.

Our video case study on the importance of raising awareness of BLS from the Italian National Union of Driving Schools and Motor Vehicles can be watched below...

Learn more about post-crash care

We recently organised an online webinar for all our members on the importance of post-crash care. Three experts gave a presentation on eCall and the challenges of firefighters and medical services. A recording of the webinar is available online here.

Sources

1Post impact care. (2023). Mobility & Transport - Road Safety. https://road-safety.transport.ec.europa.eu/eu-road-safety-policy/priorities/post-impact-care_en

2World Health Organization. (2016). Post-Crash Reponse: Supporting those affected by road traffic crashes. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/post-crash-response-supporting-those-affected-by-road-traffic-crashes

3EENA. (2023, 19 juli). ECall - EENA. https://eena.org/our-work/eena-special-focus/ecall/

4Nuyttens, N. (2022). Baseline report on the KPI post-crash care. Vias institute. https://www.baseline.vias.be/en/publications/kpi-reports/

5Calland, V. (2005). Extrication of the seriously injured road crash victim. Emergency Medicine Journal, 22, 817–821. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2004.022616

6Nutbeam, T., Boylan, M., Leech, C., & Boylan, C. (2023). ABC of Prehospital Emergency Medicine (2de editie). John Wiley & Sons.

7Rescue and Extrication | Euro NCAP. (z.d.). https://www.euroncap.com/en/vehicle-safety/the-ratings-explained/adult-occupant-protection/rescue-and-extrication/

8Revue, E. (2023). stay and play or scoop and run: EMS runs to keep you staying alive! In European Road Safety Charter. Saving lives with post-crash care. https://road-safety-charter.ec.europa.eu/content/saving-lives-post-crash-care

9Hall, A. (2016). Bystander decision-making in an emergency: a constructivist grounded theory [PhD]. Flinders University.

10Semeraro, F., Picardi, M., & Monsieurs, K. G. (2023). “Learn to Drive. Learn CPR”: A lifesaving initiative for the next generation of drivers. Resuscitation, 188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2023.109835